Newark Penn Station

Producing ‘interstitial’ atmospheres in a hegemonic reality

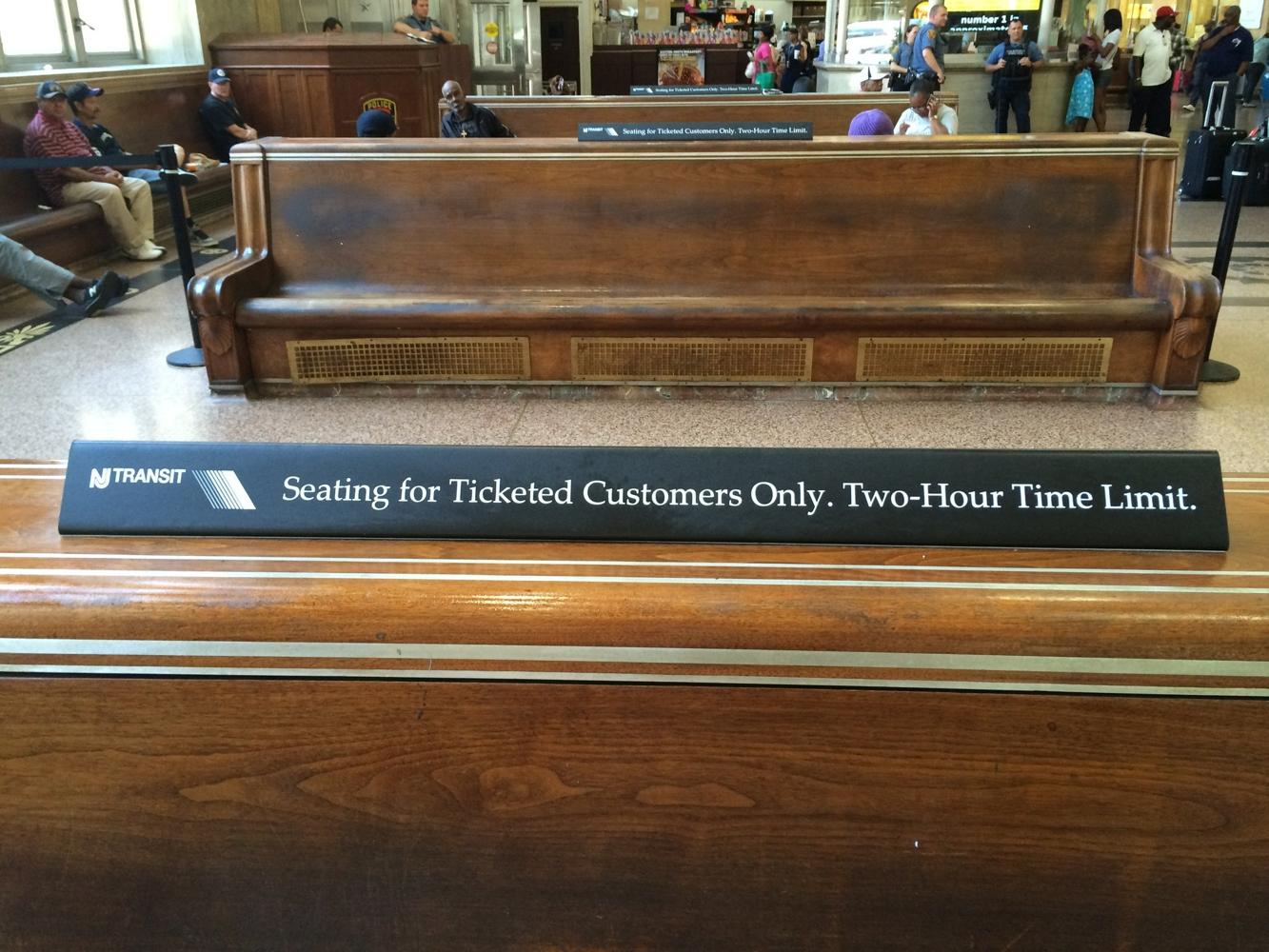

warning sign on the

benches in the NJ’s waiting hall

Since 2019, Newark

Penn Station has been undergoing a ‘modernization process’ funded mainly by the

State of New Jersey and NJ Transit. The indoor spaces of the station have been

filled with warning signs, directive panels, hostile architectures, and physical

thresholds, pushing those who experience the space to act as appropriate

‘paying passengers.’ These spatial elements dictate which behaviors are

accepted as ‘appropriate’ in the environment, and they also identify specific

spaces that are physically barred to subjectivities who differ from the ‘proper

passenger.’

![]()

![]()

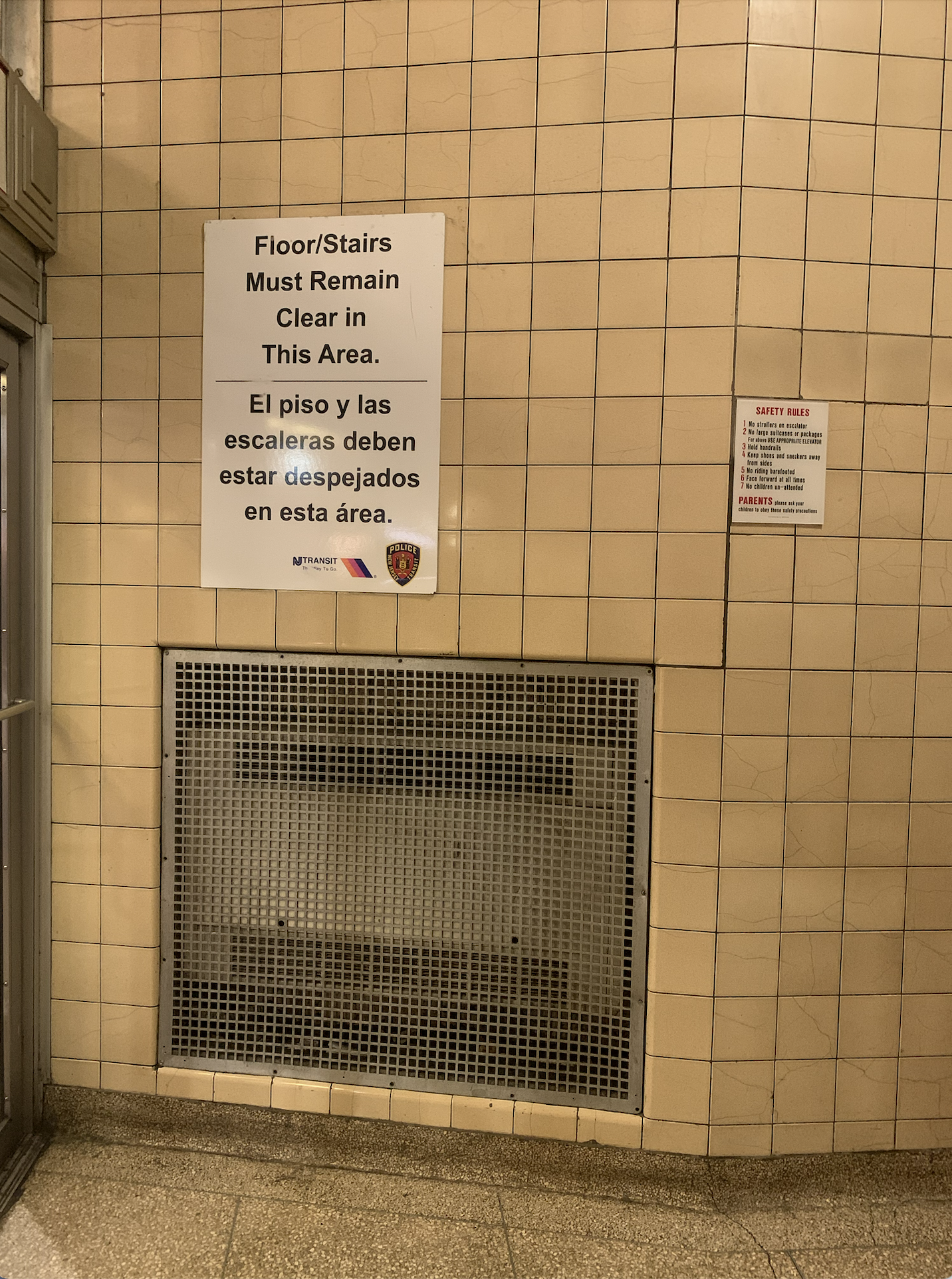

warning sign in the

stairway leading from the main hall to Track #1

The modernization of

Penn Station, an iconic and elegant landmark in Newark’s cityscape, is part of

the latest phase of urban revitalization, re-branding, and gentrification that

began in the 1990s. From an urban planning perspective, it could be argued that

Penn Station has become a ‘mobility environment,’ namely a place where “mobility

flows interconnect – such as [in] airports, railway stations, and also motorway

service areas or urban squares and parks – [and] have the potential for

granting the diversity and frequency of human contacts that are still essential

for many urban activities” (1). Thousands of passengers utilize Penn Station’s mobility

infrastructures daily, from the PATH and Northeast Corridor trains to the

Newark Light Rail’s two lines.

The station’s visible

cleanliness and perceived safety are maintained largely through the presence of

the aforementioned structural thresholds and signage, as well as by armed

policemen and private guards patrolling the station at all times. This well-disciplined

atmosphere is juxtaposed to the unruliness of the living city surrounding the station,

exemplified metaphorically by the architectural features of the Gateway Center,

a complex of four buildings located just outside of the station. Connected to

Penn Station through a system of sky-bridges spanning Raymond Boulevard and

McCarter Highway, the Gateway buildings make it possible for pedestrians to enter

the buildings without ever having to set foot onto the streets of the city.

On a larger scale, the infrastructural networks converging at, and radiating from, Newark Penn Station allow paying passengers to reach discrete locations around the city without having to experience the city itself: i.e. the city as an entity suffering from decades of neglect, lack of investment, and marginalization based on infamous narratives about its urban dangers. Beginning with the (failed) urban renewal plans of the 1950s, Newark has increasingly assumed the shape of a fragmented, low-income, and exclusionary teleport city: an urban configuration in which infrastructural networks selectively connect visitors and city-users to ‘worthy’ places while ignoring the ‘useless’ and dilapidated parts of the living, breathing city (2).

On a larger scale, the infrastructural networks converging at, and radiating from, Newark Penn Station allow paying passengers to reach discrete locations around the city without having to experience the city itself: i.e. the city as an entity suffering from decades of neglect, lack of investment, and marginalization based on infamous narratives about its urban dangers. Beginning with the (failed) urban renewal plans of the 1950s, Newark has increasingly assumed the shape of a fragmented, low-income, and exclusionary teleport city: an urban configuration in which infrastructural networks selectively connect visitors and city-users to ‘worthy’ places while ignoring the ‘useless’ and dilapidated parts of the living, breathing city (2).

sky-bridge

between Penn Station and the Gateway buildings

Within this system,

Newark Penn Station functions as the central hub, the ‘door’ of a city

that is competing fiercely to regain a spot on the map of American history. To

accommodate the expectations of commuters ‘teleporting’ into the uncoupled city (3), the station instrumentalizes sensory experiences, beyond the signage

and security patrols, to enhance the feeling of orderliness and regulation.

Among the most potent techniques for producing Penn Station’s atmosphere as a

‘safety sanctuary’ is the use of smell: with the expansion of the commercial

area on the ground floor, the area is now permeated with the myriad, pleasant

smells of coffee, donuts, pizza, popcorn, flowers, and candies. The popcorn

smell in particular suffuses the ground level with a familiar, reassuring

aroma. These scents stand in jarring juxtaposition to the strong stink of

urination, litter, and burned diesel that overpower the platforms on the

station’s second floor and the outdoor areas immediately surrounding it.

warning sign positioned just outside the popcorn shop

The distasteful

smells act metaphorically to brand the people occupying those outer areas as

‘undesirable’ as well. The primary target of the station’s politics of control,

expressed through its signs and guard patrols, is the unhoused population

inhabiting the station’s outdoor spaces. During the night, dozens of people

create makeshift, precarious shelters at interstitial spots just outside of the

station, in particular under the bridges where the bus stops are located. In

daytime, especially in the early morning, it is not uncommon for passengers to

come across people inside the station holding sleeping bags or having breakfast

at the ledges that ring the station’s large hall. These transients are not

allowed to sit anywhere, but have to stand even while eating: the policemen and

the signs are designed precisely to remind them that “seating is only permitted

in designated areas” (meaning for passengers) and that the “stairs must remain

clear.” Penn Station’s indoor spaces are thus not amenable to those who did not

buy a ticket or a fast meal to be consumed while waiting for a train; the station’s

spaces are designed to be cleared of ‘unwanted’ presences as soon as their meal

is done.

![]()

![]()

checkpoint at the entrance of the NJT waiting hall windowsill with hostile architecture

checkpoint at the entrance of the NJT waiting hall windowsill with hostile architecture

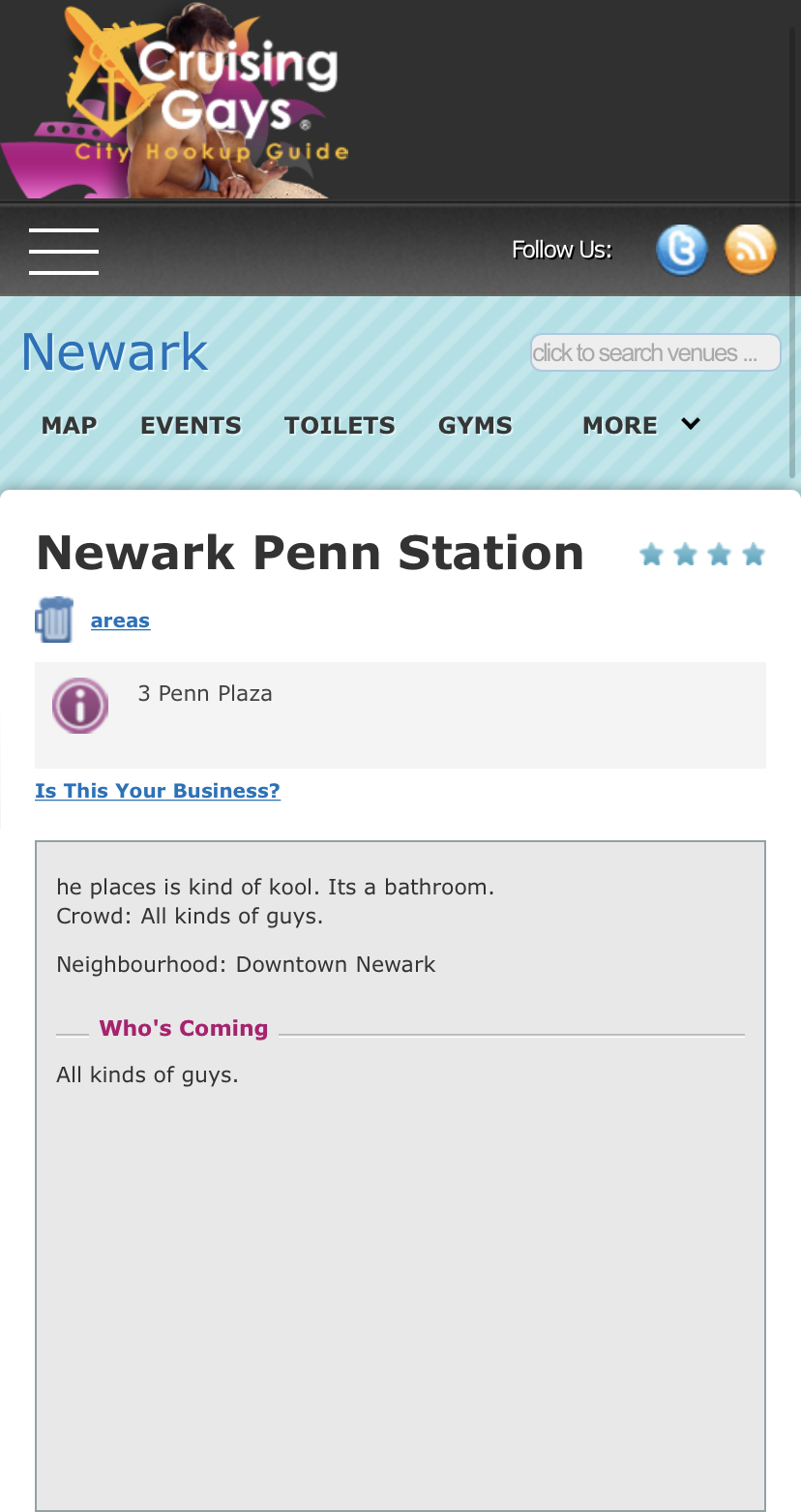

Other subjectivities,

however, have managed to turn the station’s exclusionary, controlling atmosphere

of “safety” and “cleanliness” upside down, subverting and rewriting its normative

behavioral expectations. Starting in the 1960s, for instance, Penn Station became

one of the most important and safest spaces for gay cruising and sociability in

Newark, at a time when gay men were otherwise excluded from open participation

in the public sphere. In interviews conducted by the Queer Newark Oral History

Project, several members of the LGBTQ+ community recall that the ‘gentlemen’s

bathroom’ located on the station’s ground floor functioned historically as a

place where gay men could experience their sexuality without any particular

danger (4). Today, users of websites that review and rate gay cruising spots in

Newark still describe Penn Station as one of the best spots for sexual interactions

in the city. Some users also utilize the websites’ comments section as a platform

to date other men looking for casual encounters. Tellingly, an anonymous content-creator

on a famous adult-video streaming website recently uploaded amatorial videos of

his sexual encounters in Penn Station, turning it into the main stage of his pornographic

video production.

website on which users can

rate cruising spots in Newark

As the experiences of

gay men in Newark demonstrate, hegemonic and normative urban atmospheres can be

challenged and redressed. In that particular example, the reappropriation of

space was effected by distorting and working through the ‘grammars of power’

that otherwise sustain the spatial language imposed on and throughPenn Station. This reinterpretation and reclamation of space relies on practices

that construct interstitial atmospheres within both the material and poetic functions

of the station’s spaces. Such atmospheric enclaves exist within the contradictions

that emerge from the interplay between the exclusive, unjust models of urban

development implemented in Newark and the needs and silenced claims of the excluded

communities living in the city. These practices can be interpreted as an example

of what the philosopher Leo Strauss describes as the literary techniques of ‘writing

between the lines’ (5). They may not represent explicit or loud calls for

freedom, resistance, or emancipation, but they are still able to produce

silent, ‘heterodox’ atmospheres below the hegemonic surface of reality, which can

be experienced by those who share the means – and the need – to interpret and

understand them (5).

1. Bertolini, L. and M. Dijst. (2010). “Mobility environments and network cities.” Journal of Urban Design 8 (1), 27-43, quote on 28.

2. Alioni, M. (2023). Gravitational Geometries of Exclusion: Infrastructuring (In)justice in Brescia (Italy) and Newark (New Jersey, USA). Ph.D. dissertation - Politecnico di Torino (Turin, Italy).

3. A. Mallach (2015). “The uncoupling of the ‘Economic City’: Increasing spatial and economic polarization in American older industrial cities.” Urban Affairs Review 51 (4), 443-473.

4. Queer Newark Oral History Project. Interviews can be found at: https://queer.newark.rutgers.edu/

5. Strauss, L. (1952). Persecution and the Art of Writing. Free Press.

1. Bertolini, L. and M. Dijst. (2010). “Mobility environments and network cities.” Journal of Urban Design 8 (1), 27-43, quote on 28.

2. Alioni, M. (2023). Gravitational Geometries of Exclusion: Infrastructuring (In)justice in Brescia (Italy) and Newark (New Jersey, USA). Ph.D. dissertation - Politecnico di Torino (Turin, Italy).

3. A. Mallach (2015). “The uncoupling of the ‘Economic City’: Increasing spatial and economic polarization in American older industrial cities.” Urban Affairs Review 51 (4), 443-473.

4. Queer Newark Oral History Project. Interviews can be found at: https://queer.newark.rutgers.edu/

5. Strauss, L. (1952). Persecution and the Art of Writing. Free Press.

Picture credits, in order of appearance:

1. https://www.nj.com/traffic/2017/02/constitutionality_of_nj_transits_new_waiting_room_ban_questioned.html

2. photo and closeup: picture taken by the author

3. https://subwaynut.com/njt/newark_penn/newark_penn14.jpg

4. picture taken by the author

5. https://www.nj.com/traffic/2017/02/constitutionality_of_nj_transits_new_waiting_room_ban_questioned.html

6. picture taken by the author

1. https://www.nj.com/traffic/2017/02/constitutionality_of_nj_transits_new_waiting_room_ban_questioned.html

2. photo and closeup: picture taken by the author

3. https://subwaynut.com/njt/newark_penn/newark_penn14.jpg

4. picture taken by the author

5. https://www.nj.com/traffic/2017/02/constitutionality_of_nj_transits_new_waiting_room_ban_questioned.html

6. picture taken by the author

Mapmaker: Marco Alioni

Posted 5/2/2023

Posted 5/2/2023