The Maps

Maps below: Abstractions, Threads, Newark 2000, Soundless City 1 + 2, Fugue No. 7 , Penn Station

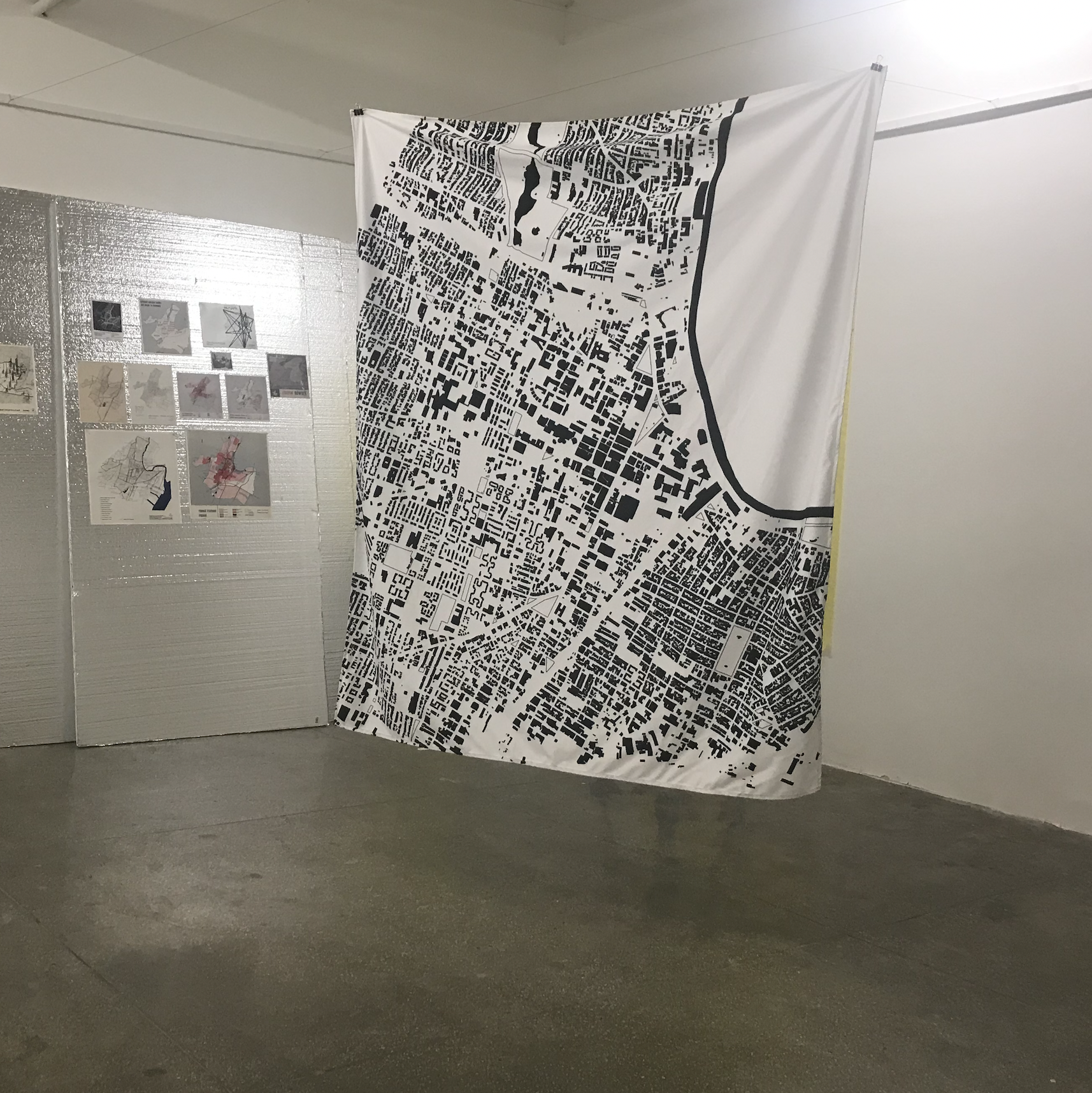

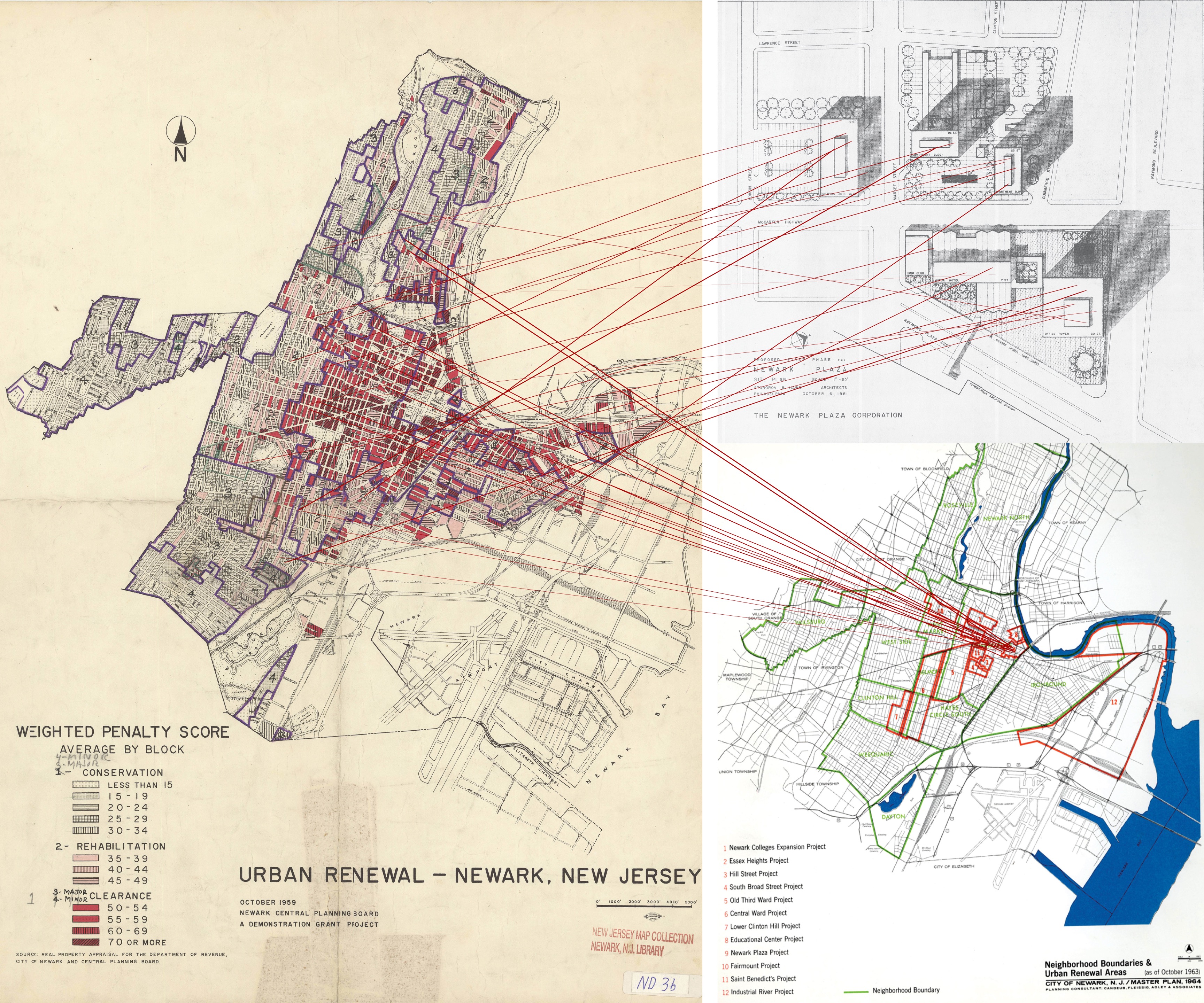

Many threads connect a city, but in 1960s Newark, urban planners focused mainly on the city’s financial ties, arguing that a strong economy would expand the city’s employment options, tax base, and vital services. They regarded prestigious urban renewal projects, like the Newark Plaza shown here, as serving the city by supporting upper income residents and business interests that would boost the economy. The relationship between the Central Business District and the city was, in their view, reciprocal, symbiotic, and therefore equal, as represented here by the threads running out from the Newark Plaza. In reality, though, the Newark Plaza distorted the relationship between city and CBD: while workers were drawn to work in the CBD from all over the city, that workspace was small and restricted, which pressed the city into service of an isolated elite. Rather than spread employment throughout the city, urban renewal funds were used to concentrate power in the hands of the business elite, creating distortions in commuting, food deserts, and gentrification for other residents. This distortion of scale and purpose is represented by the second set of threads, running from all across the city to a tiny spot at the heart of the CBD.

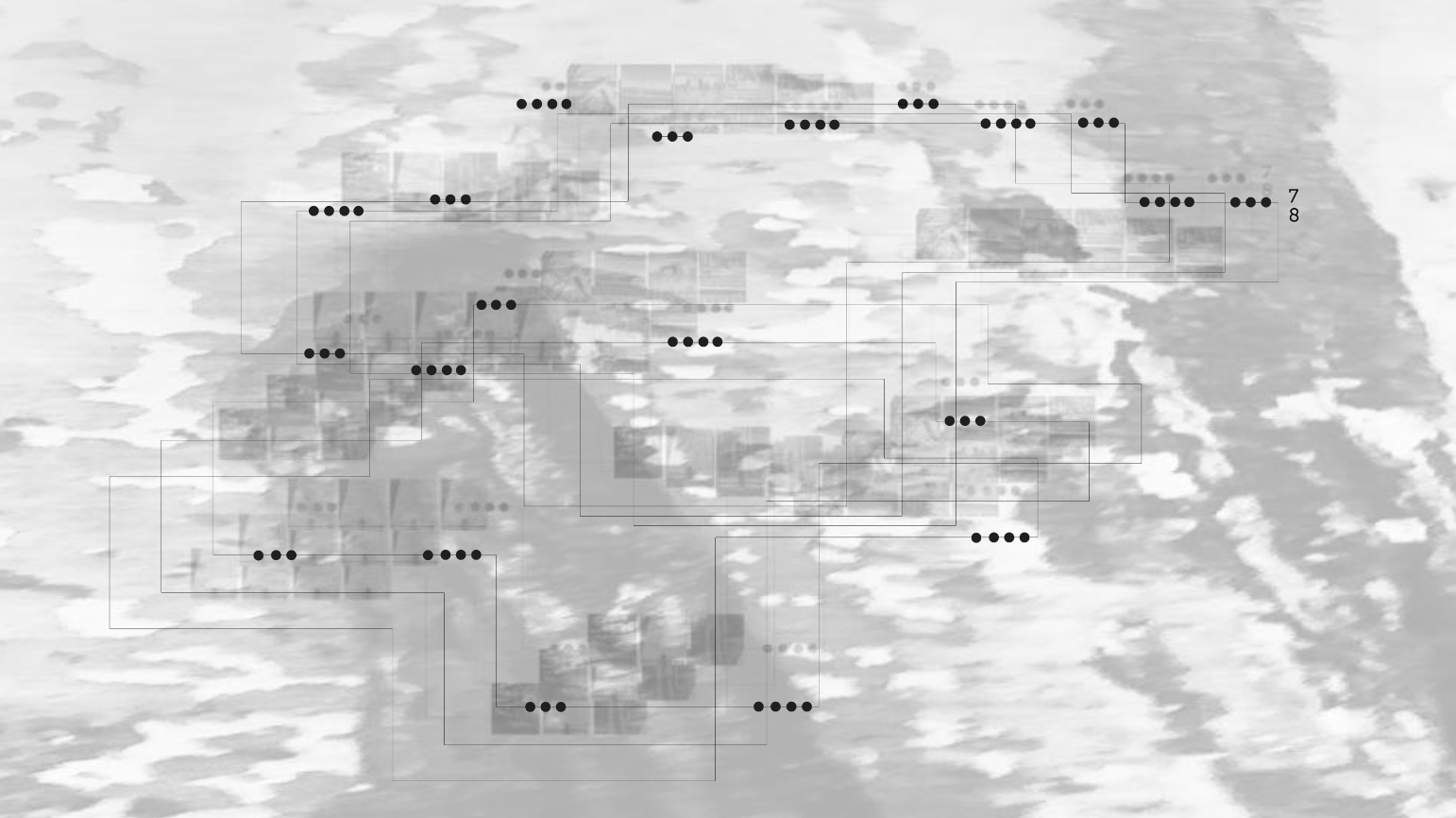

What is a map? A document of observation, maybe. I like to think of a map as a musical score. It provides a set of guidelines for the performance of movements in time and space. Each performance has its own dynamics, which operate around, through, and beyond the temporal and spatial logics we construct (1).

This map is a notation of movements performed around and within the parameters of what, out of a continuous, ongoing landscape, has come to be defined as “Newark.” The arrangement of the notation is my own, as is every map—a reflection of subjective observations. It allows, I hope, for spontaneity—in the ways I look at the landscape as it passes by the train window, in the conversations I have at the market or the coffee shop on Halsey Street. With an embrace of spontaneity, creativity, experimentation, contradiction, and difference, I resist the tendency for a map to become entirely stable or uniform. Part of this resistance is an acknowledgement that my map is one of multitudes, a number of lines in a vast polyphony of routes. This map attempts to document an intensity of attention. Images taken in and around Newark exist under the overlaying image of a tree. Train tracks and foot steps laid down become indistinguishable from the tree’s bark. The images dissolve into a rhythmic dynamics. The logic of the lines and the meter becomes irrelevant. The map is re-created every time.

1: Larry Richards, “The Anticommunication Imperative,” inCybernetics and Human Knowing (2010).

Since 2019, Newark Penn Station has been undergoing a ‘modernization process’ funded mainly by the State of New Jersey and NJ Transit. The indoor spaces of the station have been filled with warning signs, directive panels, hostile architecture, and physical thresholds, pushing those who experience the space to act as appropriate ‘paying passengers.’ This map indicates where those controlling elements are positioned, distinguishing between those that dictate which behaviors are accepted as ‘appropriate’ in the environment, and those that identify spaces that are physically barred to subjectivities who differ from the ‘proper passenger.’ The discourse of safety that underpins these acts of control and exclusion took on a very different complexion in the gay scene of the 1960s and onwards: people in the community often recall Newark Penn Station as a safe space for sociability and cruising, at a time when they were otherwise excluded from open participation in public sociability.

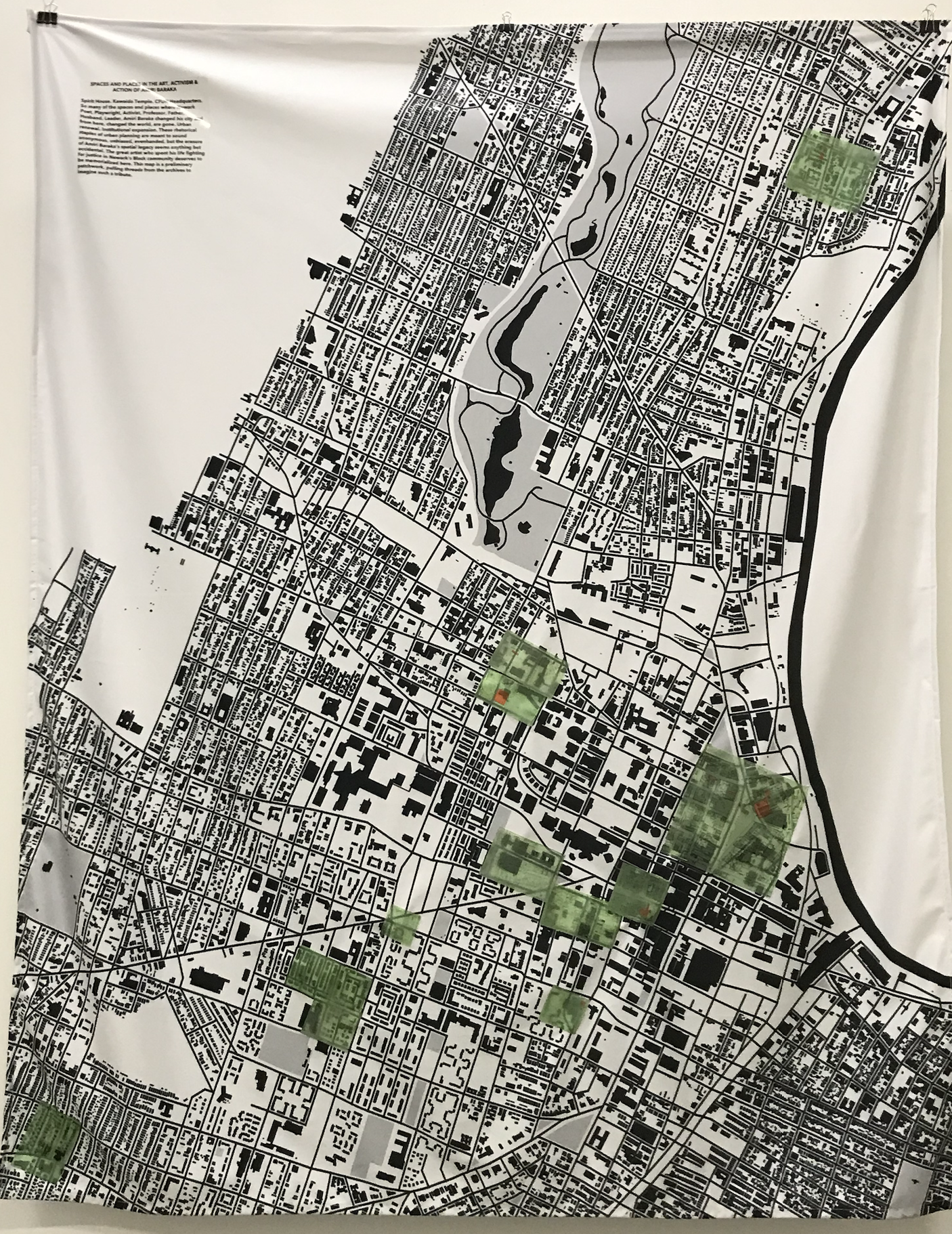

The soundless city of Newark’s urban planners negated and neutralized the existing community. In the planners’ imagination, the city needed to be cleared out so that proper populations, sounds, and behavior could replace the improper ones. In the planners’ words, they would replace blight with high culture. The city was already full of sounds, though. In these two maps, the voices of those living in neighborhoods repopulate the barren urban renewal map with waves of human sounds.

The three Soundless City maps reflect the richness of sound in the existing community. As Nathan Heard said about his upbringing in Newark in the 1950s, music was the core of his neighborhood, deteriorating though it was: “At the time I knew [the jazz vocalist] Jimmy Scott he was sort of like this neighborhood, full of life, full of people, and full of music. Music was everywhere.” In these maps, the voices of those living in neighborhoods repopulate the barren urban renewal map with sound and take possession of the space.

![]()

Culture as a tool for colonization, through the erasure of existing residents, was thus central to official efforts to wrest the city’s meaning away from its (unwelcome) inhabitants. To resist this erasure, the Place in Progress map layers its meaning on top of the Soundless City map to amplify the city’s residente cultures in another way. It asserts that every city is a work in progress created by its residents in spontaneous ways, whether through formal artistic production or the exuberance of street art like graffiti.