Site Lines

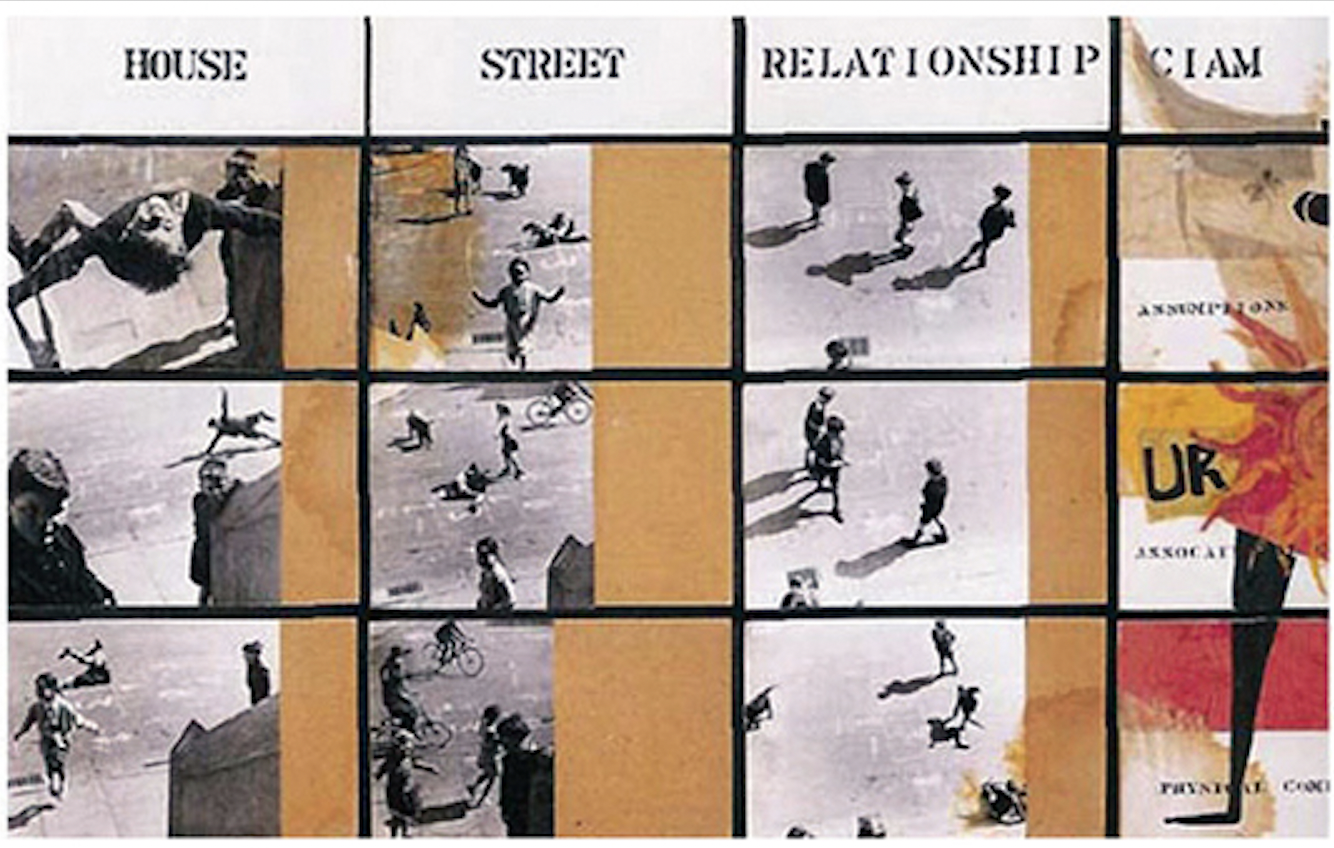

In 1953, Alison and Peter Smithson rendered a

unique grid for the CIAM 9 conference in Aix-en-Provence. Beginning at CIAM 7

in 1949, Le Corbusier had insisted that all members of CIAM (Congrès

Internationaux d’architecture moderne) submit grids as “thinking tools” for

town planning projects in order to bind participants to the functionalist

planning model. As a critique of the traditional grids’ technocratic rigidity,

the Smithsons based their grid on an idealized vision of children’s play. The

city as playground was a dubious concept in 1960s Newark, though, as the city’s

racial bias belied the Smithson’s cheerfully homogenizing vision of a community

of equals with equal right to the city.

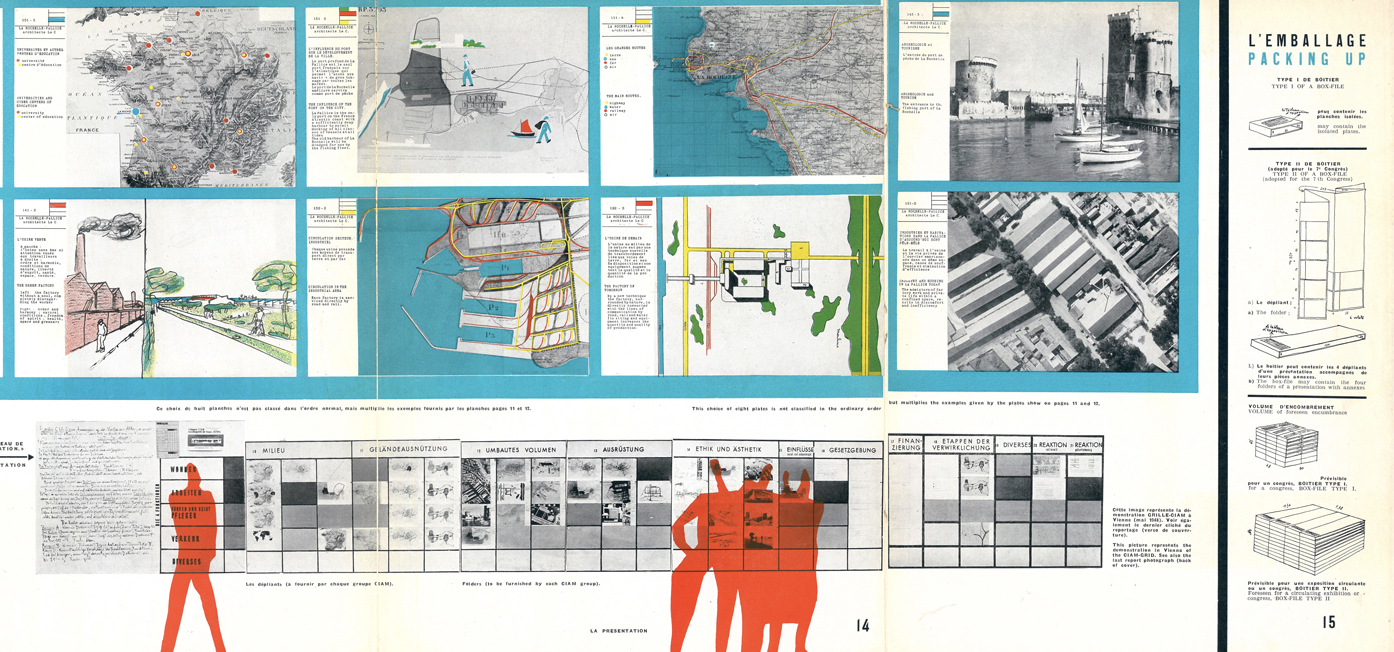

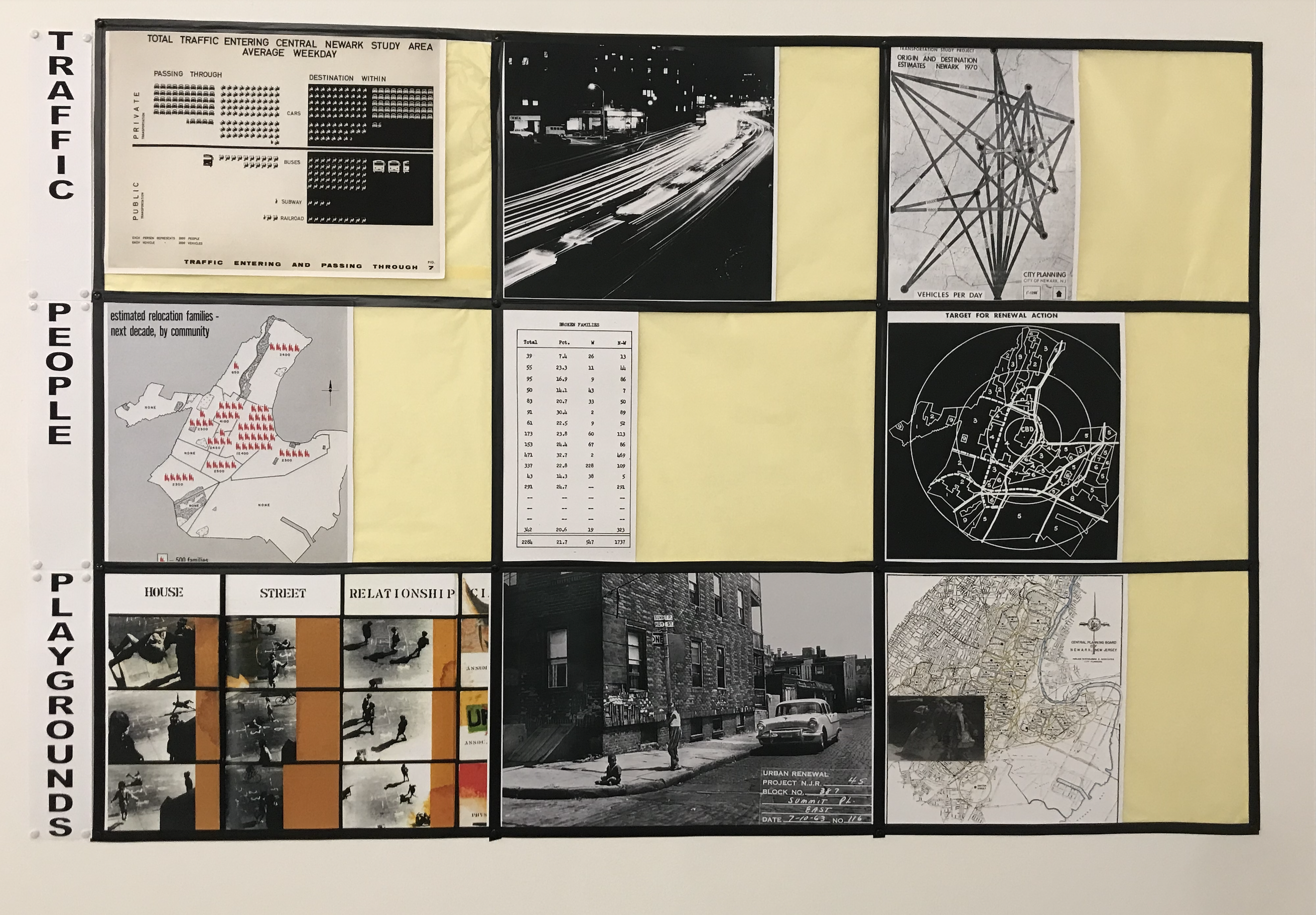

The Grille/Grid here can be read from the bottom up:

Playgrounds: Juxtaposed against the Smithson’s sunny image of children playing, the African American children in the middle image were photographed by city authorities to justify the expansion of NJIT’s campus in urban renewal project NJR-45. The children’s abandoned appearance and lack of play or joy was used as evidence of moral blight, which was then used to clear their families out of their homes. Replacing them, in the city center, were the children and families desired by the white planners, like those in the right-hand image, photographed for the 1964 Master Plan and overlaid onto a diagram of city playgrounds.

People: The tendency to code families as objects of data and displacement runs like a red thread through Newark’s urban renewal plans. Residents were abstracted in multiple ways, as aggregate figures on displacement maps and in statistics that coded them as dysfunctional and therefore ripe for state intervention. The intention was to clear them out of their neighborhoods without their input, as Newark became a target for repossession by white residents.

Traffic: The left-side traffic diagram resembles the abstracted families directly below, and not by chance. The discourse of traffic was the dominant theme in Newark’s urban renewal plans, and was accordingly projected onto families in a similar functionalist manner. Traffic ruled Newark’s urban renewal vision: it was the crux for bringing shoppers and residents into the city to revitalize the economy and expand the city’s tax base. Traffic had to flow freely and dynamically, as the center image from the 1964 Master Plan wishfully shows. Any blocks to traffic – including people – could lead to an explosion, as broadcast in visceral fashion by the right-side traffic map.

Playgrounds: Juxtaposed against the Smithson’s sunny image of children playing, the African American children in the middle image were photographed by city authorities to justify the expansion of NJIT’s campus in urban renewal project NJR-45. The children’s abandoned appearance and lack of play or joy was used as evidence of moral blight, which was then used to clear their families out of their homes. Replacing them, in the city center, were the children and families desired by the white planners, like those in the right-hand image, photographed for the 1964 Master Plan and overlaid onto a diagram of city playgrounds.

People: The tendency to code families as objects of data and displacement runs like a red thread through Newark’s urban renewal plans. Residents were abstracted in multiple ways, as aggregate figures on displacement maps and in statistics that coded them as dysfunctional and therefore ripe for state intervention. The intention was to clear them out of their neighborhoods without their input, as Newark became a target for repossession by white residents.

Traffic: The left-side traffic diagram resembles the abstracted families directly below, and not by chance. The discourse of traffic was the dominant theme in Newark’s urban renewal plans, and was accordingly projected onto families in a similar functionalist manner. Traffic ruled Newark’s urban renewal vision: it was the crux for bringing shoppers and residents into the city to revitalize the economy and expand the city’s tax base. Traffic had to flow freely and dynamically, as the center image from the 1964 Master Plan wishfully shows. Any blocks to traffic – including people – could lead to an explosion, as broadcast in visceral fashion by the right-side traffic map.

Eva Giloi: Hedges, Windows, Whispers

Kevin Rogan: Newark 2000